In this article:

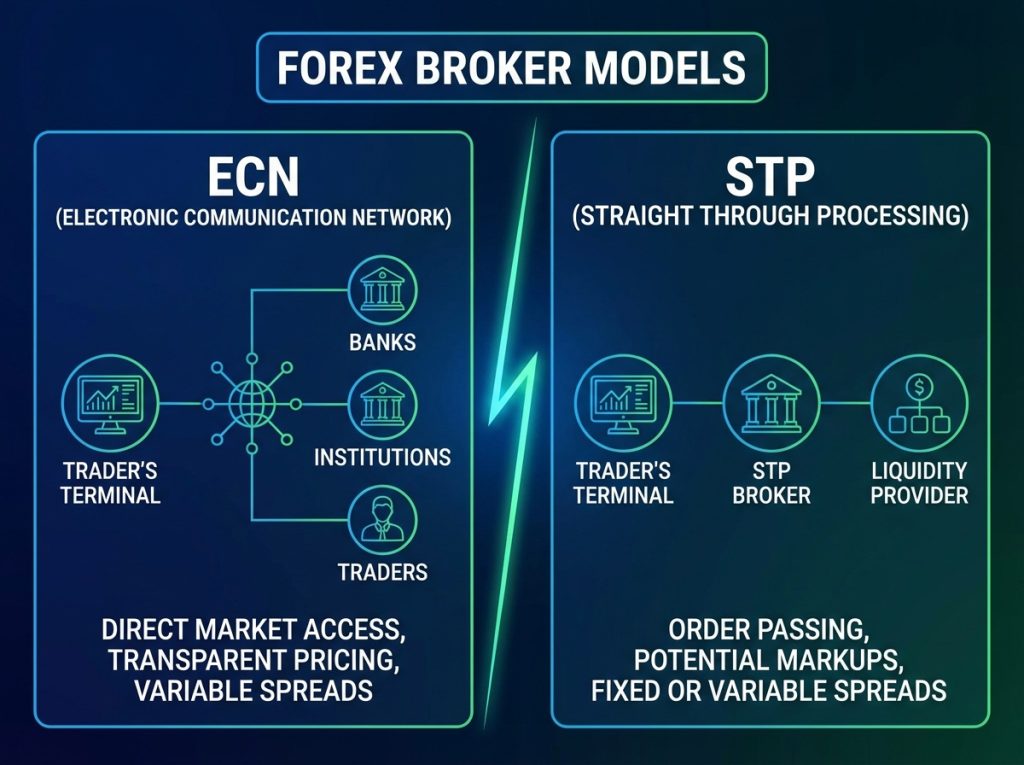

When you trade forex the broker you pick defines more than just the screen you click; it determines how your orders are priced, where they go, who sits opposite your trades, how fills behave under stress, what costs you actually pay, and what happens if markets gap. “Dealer desk,” “ECN” and “STP” are descriptive labels for different execution and business models used by forex brokers. They are not merely marketing tags — they imply different plumbing, priorities and failure modes — and understanding the distinctions is essential if you want predictable execution, realistic cost estimates, and a broker that matches your trading style.

This article explains each model in plain operational terms, compares how they differ on pricing, routing, liquidity, execution quality and conflict of interest, discusses which styles of trading suit each model, and gives practical tests and due diligence steps you should run before funding a live account.

If you are looking to find a broker to open an account with, then this article will be of little help for you. At least if you already know what kind of account you want to open, it makes it easier. If that is the case, then I recommend that you visit BrokerListings.com. BrokerListings.com is a website that makes it easy to compare different brokers side-by-side without having to switch between different pages.

A short conceptual framing

All three models answer the same practical question: when you click “buy” or “sell”, what happens next? Does the broker take the opposite side and internalise your order? Does it convert your order into a single wholesale order to a liquidity provider? Does it split your order across many liquidity venues and post it into an order book? The answer affects spread, commissions, slippage, requotes, potential for execution latency, and whether your broker has a direct economic interest in your losses.

Understanding the models reduces to three linked domains: execution path (how orders travel), liquidity source (who supplies prices and size), and business model (how the broker earns money). Each model balances those domains differently.

Dealer desk (market maker) — structure and practical behaviour

A dealer desk broker — often called a market maker — typically runs an internalised pricing engine and often (but not always) acts as the counterparty to client trades. The broker either provides prices from a proprietary pricing engine or aggregates feeds and then posts the bid/ask you see. When you execute, the broker can match you internally with another client, hedge some or all exposure externally, or keep the risk on its books.

Operationally this model usually means consistently available two-sided markets and often no direct variable commission; costs are embedded in the spread. Execution is immediate because the broker is quoting the price. That immediacy can be valuable for small retail trades or when liquidity is otherwise sparse. But it also creates an inherent conflict of interest in the pure principal model: if the broker keeps client risk, then client losses are, in an economic sense, broker gains. Good firms mitigate the conflict by hedging flow with many liquidity providers, transparent pricing and by separating risk management desks, but the structural potential for conflict remains.

Market makers can offer advantages: guaranteed liquidity at displayed sizes, limited or no requotes in many cases, and often wider product sets (exotics, smaller pairs) because the broker can warehouse risk. The downsides are visible when market stress hits: spreads can widen materially, slippage may be larger on execution than on an ECN, and order fills can be subject to internal repricing or discretionary intervention if the broker’s risk desk decides to manage exposure. For certain account types the broker may impose minimum hold times or restrict particular strategies (scalping rules), and internalisation can produce different execution for very active accounts.

Straight-Through-Processing (STP) — the intermediary model

STP describes a routing model rather than a precise legal structure: the broker takes client orders and forwards them to external counterparties (liquidity providers) without manual handling on a deal-by-deal basis. An STP broker typically aggregates liquidity from a small number of banks or electronic liquidity providers and then presents a blended price to clients. When an order arrives it is passed through to one of the upstream providers, often chosen by a pricing engine that selects the best available provider or rotates flow across the pool.

The STP model reduces some direct conflict of interest because the broker is not necessarily the counterparty on each trade; the broker’s revenue comes from the spread markup or from a small commission built into routing. However the model creates a different set of operational tradeoffs. Prices shown to clients may be a blended feed with added markups; the broker can choose routing priorities; and when a provider refuses a fill the broker may re-quote, reject, or attempt to execute with another provider. Requotes and rejections are more common than on ECN models but typically less frequent than with a market maker that manually intervenes.

STP is a pragmatic middle ground: quicker implementation and easier product coverage than full ECN, with less principal risk than a market maker. For many retail and mid-size professional clients STP offers acceptable execution with simpler pricing, but execution transparency and routing fairness are variable across providers. The key question is whether the broker uses the same liquidity pool for micro and standard accounts, whether it discloses routing rules, and whether it hedges flow externally or internalises when it suits the desk.

ECN (Electronic Communication Network) — order book style aggregation

ECN models route orders into a multi-participant matching environment where liquidity providers and other participants post quotes or limit orders and orders are matched electronically. In the classical ECN model your order is exposed to an on-screen or on-protocol pool and is matched against other participants. Execution tends to be venue-level so the price you receive reflects the aggregated liquidity available at the moment your order is processed.

ECN models usually separate spread and commission explicitly. You see raw liquidity (tight interbank spreads when available) and then pay a per-trade commission or a transaction fee. ECN execution is often the most transparent: fills are sourced from the order book rather than being manufactured by a dealer, there is less scope for discretionary repricing, and the venue’s visible depth can be inspected before placing larger orders. For high frequency or professional traders ECN is attractive because it supports DMA-style trading, true market access, and often deeper depth in major pairs during liquid hours.

The ECN advantage shows up when liquidity is abundant: lower effective spreads and tight fills. The disadvantage appears in thin times: without a market maker to take the other side, large orders can suffer severe slippage unless the ECN aggregates liquidity across many providers. ECNs can also expose traders to higher variable cost per ticket because commissions stack up for frequent trades. Finally, some ECNs impose minimum order sizes or charge higher fees for small ticket flow, which matters for micro accounts.

Pricing and cost differences explained

All three models present the same superficial costs — spreads, commissions, financing — but the composition differs.

Market makers typically embed cost inside wider spreads and may have zero or low overt commissions. The spread is the primary cost and it can widen automatically when the broker’s risk desk or pricing engine reacts to volatility.

STP brokers often show a slightly widened spread relative to raw interbank quotes and may take a small commission or include hidden markups. The actual cost is a blend of spread plus any per-lot charge and can vary by instrument and account tier.

ECN brokers tend to show raw, tight spreads with explicit per-lot commissions. Low spreads plus commission can be cheaper for larger traders who execute many pips per trade, and who can aggregate commission efficiently; for scalpers with tiny tick targets, commissions can make ECN execution uneconomic unless the ECN offers rebates or VIP pricing.

It follows that you must compute expected round-trip cost in the currency units you trade, not in pips alone. A one-pip spread on EURUSD at 0.01 lot size is a different dollar cost than a one-pip spread on a 1.0 lot size; commissions matter more the more tickets you place. Also consider hidden costs: withdrawal fees, inactivity fees, exchange or exchange-like levies on some instruments, and the economic impact of requotes and slippage under stress.

Execution quality: requotes, slippage, latency and partial fills

Execution quality is a function of market microstructure and the broker’s routing. Dealer desks can offer guaranteed fills at the displayed price but sometimes do so by internalising and then adjusting client blotters; that can lead to discretionary fills or re-pricing at times of stress. STP brokers will route to external providers and may requote if upstream liquidity vanishes; ECN systems, by contrast, either fill against existing orders or do not, producing fewer requotes but potentially larger slippage if depth is insufficient.

Slippage can be favourable or adverse. ECNs can give favourable slippage when there is hidden liquidity or when the next tick favours your side, while market makers can choose to offer positive slippage as a competitive service or to protect the desk in other cases. The practical takeaway is to measure actual execution over a representative sample of trades at your intended size and time of day. Watch how execution behaves around economic releases, and test how stops execute during volatile windows — different brokers handle stop logic in different ways (market stop vs guaranteed stop), and those rules materially affect realized slippage.

Latency matters most for high frequency and news-sensitive strategies. ECN infrastructures optimized for low latency are better for scalpers trying to capture microstructure moves, while dealer desks that stabilise prices can be acceptable for swing traders who prioritise certain spreads and guaranteed fills over the last millisecond of latency.

Conflict of interest and hedging practices

The conflict story is straightforward. A pure market maker that keeps client flow on the house has an economic incentive that can diverge from the client’s interest. An STP broker that hedges some flow and internalises the rest creates a mixed incentive. An ECN provider that simply posts liquidity for a fee has minimal direct conflict because the venue does not profit directly from client trading outcomes, although other participants in the ECN might.

That said, “conflict” is not determinative; many reputable market makers manage conflicts via transparent hedging, disclosure, and by routing net client exposure to external LPs. What matters in practice is disclosure and behaviour under stress. If a broker refuses to disclose routing rules, consistently widens spreads only on losing clients, or imposes opaque restrictions that disproportionately affect active traders, treat those as red flags regardless of the advertised model.

Suitability by trading style

Scalpers and latency-sensitive intraday traders usually favour ECN execution because of the raw spreads, access to depth, and predictable matching. They need low latency, predictable slippage statistics, and explicit commission structures they can model.

High frequency algorithmic systems often prefer ECN or institutional STP with DMA/ FIX access because they need consistent routing, historical tick data, and co-located or VPS options for minimal round-trip time.

Swing traders and position traders who hold across days may prefer STP or market makers that offer predictable overnight financing, wide product coverage, and solid customer service. For them, small differences in millisecond latency are irrelevant while predictable overnight rates and corporate action handling matter more.

New retail traders often accept market maker accounts because they reduce the chance of immediate rejection, and because they combine simple pricing and often low minimum deposits. The tradeoff is higher long term cost and the need to verify fairness objectively.

How to test and verify a broker’s claims

Do not rely on marketing copy. Run a funded trial with live money sized to a meaningful portion of your target allocation and test the following explicitly: spread distribution at the tickets and times you will trade; execution quality (track entry price vs fill price and slippage distribution); behavior across volatile events (economic releases); stop and limit fill mechanics; time and success rate of small withdrawals and KYC processing; and how the broker handles a complaint.

Collect data: log timestamps, instrument, quoted spread at the time of order, executed price, slippage and any error messages. Compare micro and standard accounts if the broker offers both. Ask for written explanations of routing, matching and whether your account is executed on the same pool as the broker’s institutional clients. If answers are vague or evasive, consider that a material governance weakness.

Regulatory and counterparty risk

Check the legal entity that will hold your funds, its regulator and the protections that regulator offers. An FCA-authorised broker will have different investor protection and segregation rules than an offshore broker. Regulation does not guarantee good execution, but it helps for dispute resolution, custody rules and minimum capital standards. For high volume or institutional activity consider prime brokerage relationships or liquidity aggregation services that offer explicit credit lines and clearer legal protections.

Practical decision checklist (brief)

Choose an ECN model if you need raw liquidity, transparent routing and lowest spread plus explicit commission and you can tolerate explicit commissions and potential slippage on large tickets. Choose STP if you want an operational middle ground — external liquidity without the cost and complexity of full ECN — and if you prioritise simplicity and product coverage. Choose a dealer desk (market maker) if you value guaranteed fills, low minimum deposits and instantaneous execution for small trades, but be prepared to verify fairness empirically and to accept potential conflicts.

Final note on scaling and adaptation

Whichever model you start with, plan for scaling. Execution characteristics that look fine at tiny sizes may not scale linearly: spreads, depth and routing can change with size. Always stage increases in capital, compare fills as you scale, and maintain the option to move to another legal entity or account tier if execution changes. The right broker is the one whose real world execution and governance you can verify, whose remediation process works when things go wrong, and whose product suits the time horizon and style you actually trade rather than the one the marketing team imagines.

Choosing between dealer desk, STP and ECN should not be an ideological decision. It is an operational one about latency, transparency, cost composition, and trust. Know the plumbing, measure it in practice, and pick the model that aligns with your execution needs and your appetite for the particular operational risks each model brings.